By JP Snow, Principal & Founder at Customer Catalytics, August 15, 2024

This article is part of our Customer Concepts series, covering core ideas inherent to Customer Catalytics’ Customer Creation Model as necessary for driving growth, retention and scale.

Needing Segmentation is a Sign of Growth

Esther Diener operated a popular restaurant that thrived for nearly thirty years amidst the rural communities of northwest Ohio. The wife of a Mennonite minister, Esther knew her community, and she saw opportunity in the lack of dining options where locals could find quality food and a familiar experience without a long drive. She acquired a blocky, brick building on a two-lane highway at the midpoint between two of the larger towns in the area. The building had formerly housed a plumbing business. In two directions, cornfields stretched to the horizon. Das Essen Haus (German for “The Food House”) served American fare in a style familiar to the area’s German-descended culture. People came for the food and the atmosphere. And they came because of Esther, who was always smiling and knew her regulars well.

Esther usually stationed herself near the entrance, but she constantly circulated, making sure the experiences met her expectations and watching for new opportunities. Most of the patrons were families and retirees, but the restaurant easily served a second customer segment of delivery drivers and tradesmen. The layout of the building included a corner near the back parking lot that was big enough for trucks and was directly accessible through a single back door. Esther set up large tables where these diners could seat themselves for breakfast or lunch. Das Essen Haus also hosted a monthly T-Bone Club where local farmers could enjoy a meal and some camaraderie in their own dedicated space. Esther continuously identified customer segments with unmet needs and developed additional offerings to serve them. Other innovations she made over the years included a community table concept, a food truck and private meeting space. She succeeded by being constantly present, engaged and observant of her customers.

What Esther didn’t need was a segmentation model. Small businesses and early-stage companies often succeed by serving a single segment they know well. A small company with big aspirations might include segment expansion in their business plan, but they just as often reach viability through a single target audience and navigate through the intuition of a founder, who knows their best customers individually. Segmentation becomes useful when the customer base gets too large to understand and personalize, or when the service experience becomes more distributed across more people and systems.

Segmentation Is a Tool for Organizing Customer Needs

I’m taking a broad view of segmentation in this article, covering both qualitative and quantitative approaches and providing options accessible to small and medium-size businesses. Corporate giants with millions of customers often think of segmentation as an analytics technique. Subsets are generated based on traits that result in the strongest similarities within each group and the strongest differences between groups. At the simpler end of the spectrum, innovation projects often begin with personas defined to force specific and divergent thinking across the full range of users. Customer segmentation involves identifying and defining distinct types of customers for the purpose of:

- Organizing customer needs into a manageable set, based on shared traits relevant to offer development and experience design

- Ensuring comprehensiveness by representing the full range of customer types and needs

- Discovering ROI opportunities based on differentiated economics, feature demand, channel preferences and price sensitivity

- Providing a mechanism for operationalizing service models, product design and experience delivery, through automation at the individual customer level

Put another way, segmentation helps a business create and keep customers by organizing a large and varied customer base into a manageable set of reasonably similar targets small enough for planners to “get their head around.”

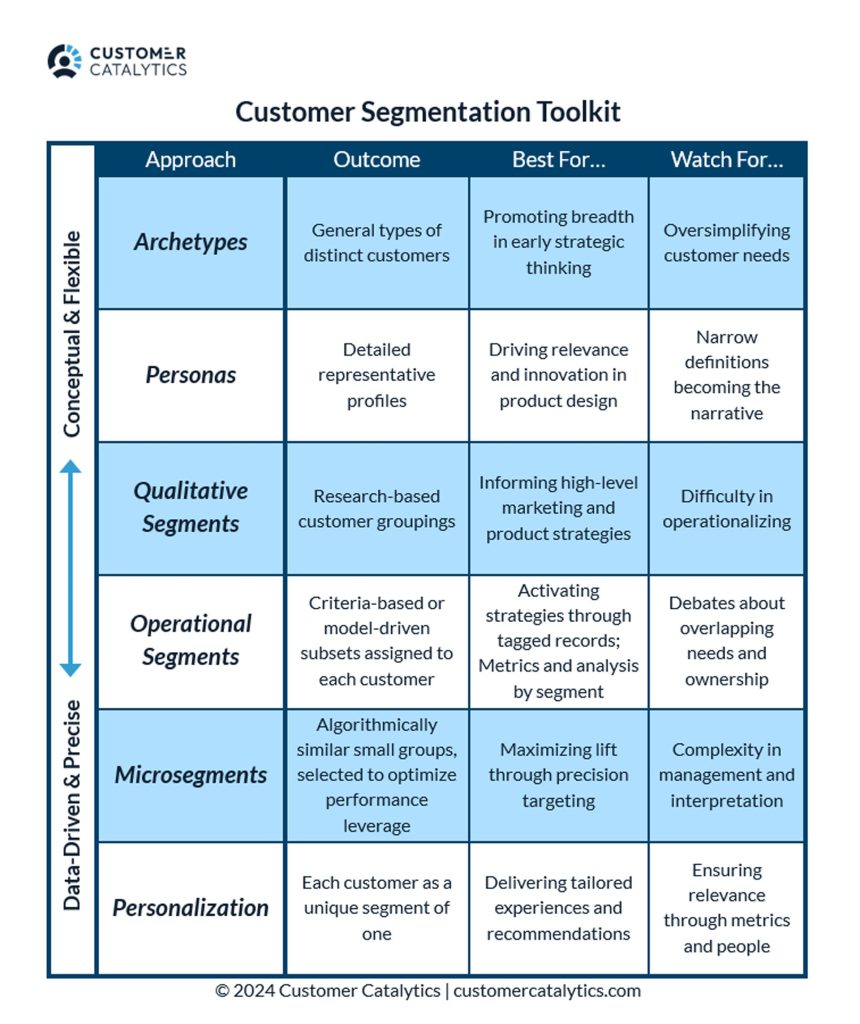

Market researchers, data scientists and industrial designers have created entire disciplines focused on customer segmentation. The most robust segmentation models draw from all three of these fields. In practice, segmentation typically leverages one of several approaches depending on the available data sources and the use case at hand. I’ve organized the options into a toolkit of six approaches: archetypes, personas, qualitative segments, operational segments, microsegments and personalization.

Choose the Method that Meets the Need

Archetypes and personas involve identifying representative types or describing specific individuals that exemplify combinations of characteristics and needs relevant to a business’ offerings. Archetypes are more general, which means they can be named and changed quickly. They are useful for injecting a broader range of thinking into strategy and product development processes, especially in the early stages when insights are scarcer. Archetypes can generate valuable hypotheses about potential sources of demand, which should be validated and refined through tracking and research. Personas are more precise, based on authentic and sometimes colorful traits. They typically include specific details based on an actual customer or what is representative of a group. They often get a human name instead of a segment label. Personas are more useful when based on in-depth research of the target audience.

To illustrate archetypes and personas, consider how they are likely being used right now as hundreds of new ventures seek to cash in on the current hype around artificial intelligence. Let’s explore the case of a start-up developing an AI product to help restauranteurs match trends in dining interest to trends in food costs. Such a solution would support menu innovation through the practical lens of the thin margins inherent to the restaurants. In the earliest discussions, our start-up might keep a few archetypes in mind to promote breadth in their thinking and selectivity toward a main direction. Example archetypes might include “Tech-Savvy Metro-ists: Experienced restauranteurs running a family of concepts in a major metro area,” and “Solo Chefs: Mom and pop establishments challenged to innovate while reducing costs.” A series of archetypes can be enough to help strategists test their model and ask themselves questions like “How user-friendly should our interface be?” and “Do we know enough about our customers’ potential budgets?” A persona would have more detail. For example: “Martha, age 42, is opening her fourth restaurant concept, capitalizing on her local reputation for creative fusion of ethnic flavors and local ingredients. She recently delegated menu planning across her head chefs, who think about food more than economics…”

Persona experts rely on repeatable methodologies that are both art and science. They often hold strong opinions about how specific to be and whether the person described must be a real person vs. a composite. Strictly speaking, personas aren’t a form of segmentation, but they do make segmentation more actionable and relatable. Personas serve as a bridge between abstract segment definitions and the real-world customers they represent. By creating detailed, humanized representations of each segment, personas help teams across the organization internalize customer needs. Businesses that have a formal segmentation often develop a persona to represent each group. Businesses that lack the customer population and tools needed for formal segmentation can still use personas to reflect the distinct customer types they serve.

Both qualitative and operational segments involve dividing the entire customer base into distinct, non-overlapping groups based on specific criteria. Qualitative segmentation uses insights from market research to identify types of customers. Depending on the objectives and sample sizes, the research may use advanced quantitative techniques. The outcomes are “qualitative” because they describe the main qualities of each sub-segment, often without a direct mapping to each individual customer. Sometimes the approach is open-ended, allowing the data to reveal distinct types. In other cases, the research is commissioned to solve a specific problem, like service model design or product line definition. A classic example is the consumer budget-focused segmentation General Motors developed as it consolidated Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac into one company. They aligned each of these brands, in that order, to a “pyramid of demand” arrived at via a “comprehensive study of the total automobile market.” Chevrolet was the entry level. At the other extreme, Cadillac was for the mature couple who had arrived.[1] This segmentation informed marketing strategy and facilitated setting advantageous price points relative to competitors’ less granular approach. The best qualitative segmentation models rely on deep market research to ensure the segments reflect the most relevant needs in accurate proportion to the actual customer base.

With operational segments the defining logic is based on business-defined criteria or a model. The definitions are specific enough that each customer’s segment can be known, tagged within customer data platforms and summarized into business metrics. Criteria-based definitions tend to be used in cases where the segmentation is driven by a strategic plan or other business structures, when the determining inputs are relatively few or when modeling is unavailable. For example, a fiberglass insulation maker might segment their B2B customers based on sector and then size. Big box home improvement retailers sell home insulation at a different scale and with different specifications compared to the insulation used in automobiles, appliances and spacecraft. The resulting segment breakouts of marketing and financial metrics would inform production planning, sales coverage and advertising strategy. To achieve mutual exclusivity, overlaps in criteria are often decided via a hierarchy, which can lead to ongoing debates about overlapping needs and ownership .

Modelled segments are built using cluster analysis and other statistical techniques. The algorithms evaluate many input variables to find the most common patterns of similarity. Additional people are iteratively added using “nearest neighbor” logic until the full base is allocated. Data scientists can tune the model by defining the desired number of segments, weighting criteria and other parameters. While customers are automatically assigned to just one segment, the underlying math isn’t always transparent. Qualitative and operational segments are typically given descriptive names that reflect the dominant traits and strategic relevance of each segment. If you’ve ever waited in line to check in at a large hotel, you can imagine how their segmentation might include groups like Leisure Couples, Road Warriors, and Conference Cohorts.

Compared to the other approaches covered so far, having operational segments offers major advantages. Strategy can be activated by delivering distinct experiences based on the segment tagged to each customer’s system record. Moreover, customer behaviors and outcomes can be reported at a segment level. The advantages are strong enough that companies often look for ways to translate qualitative segments into hard criteria. When their market research is robust enough, they may find they have enough similar fields in their customer data to replicate the patterns determined among research participants. Modeling can also be used to predict which research-based segment each customer most closely resembles. In both cases, it helps to plan ahead by providing for matching keys and gathering relevant demographics as part of a survey. Another method involves asking each customer a few questions to help place them. This approach has become more common with the prevalence of mobile apps, which are well-suited for such brief interactions.

Microsegments extend the benefits of traditional segmentation to a far more expansive level of granularity. With microsegmentation, the customer base is allocated into hundreds or even thousands of small groupings having very similar traits. The segments are identified by a number or code because there are too many for developing descriptive names – which isn’t the point anyway. Each microsegment is so similar in their needs and behaviors that they also resemble each other in their response to marketing tactics and other differentiated experiences. The growing capabilities of digital marketing and journey orchestration systems can leverage these strong similarities to discover what works and automatically apply it to others in the same or adjacent segments. What you give up in having a small number of familiar segments is gained in model precision and marketing lift.

Published microsegmentation case studies tend to focus on success at manually selecting small subsets of customers with high potential for a new product or for a campaign geared to that segment’s distinct needs. Interest in the more comprehensive, data-driven approach described above is likely to accelerate, driven by two forces. First, the new wave of generative AI techniques is providing more powerful methods that are also acclimating business users to working with more abstract logic more removed from the source. Second, microsegments are a good solution for continued privacy concerns and expanding regulations. They offer an elegant balance between customers’ demands for anonymity and marketers’ need for precision.

Personalization involves treating each customer as their own unique segment. It can also be viewed as taking microsegmentation to its full extreme. With advances in data modeling and digital technology, marketers and experience designers can skip the segmentation step and instead provide each customer with options predicted to best suit them as an individual. Recommender engines encapsulate such modeling into systems that can be integrated into a company’s CRM ecosystem, consistently suggesting the same next best actions across touchpoints, backed by consistent measurement. Personalization enables a company to treat each customer as the unique individual they are. In a sense, the customer segmentation used since the 1980s was a stopgap that enabled companies to operationalize their customer strategy until technology could provide automated decisioning at the individual level. Broader segmentation is still useful for planning and reporting. To maximize their customer relationships, companies should prefer personalization over segmentation whenever they can.

When personalization is positioned as generating tailored solutions based on how well the company knows the customer, it’s crucial that the recommendations seem relevant. Otherwise, the company is signaling how much they don’t know the customer. Research consistently shows that customer trust and business outcomes are made worse by irrelevant recommendations that claim to be personalized. Because so much is automated, it’s critical that personalized offers and experiences receive sufficient monitoring for relevance, accuracy and client satisfaction. The power to treat customers right at scale is also the power to get things wrong, at scale.

The Most Powerful Segmentation Focuses on Customer Need

Business leaders often turn to segments when they need to break a large customer base into more manageable parts. The motivation can be for allocating capacity, understanding financial results or developing a growth strategy. In a large corporation, it’s common to have special-purpose segmentations across the company. The sales leader segments by region and customer type to assign sales reps. The call center head segments by product usage and client value to optimize inbound call routing. The CMO segments by acquisition cohort and channel to understand marketing performance. These segmentations can be based on a variety of factors including geography, life stage, service consumption, subscribed products, revenue and growth potential.

In addition to these specialized segments, it’s useful to have an over-arching segmentation used across a business as the common reference point for understanding customers and mobilizing to meet their needs. The ideal approach for this master segmentation is a needs-based segmentation. Businesses create and keep customers by delivering experiences that fulfill their unmet needs. Needs-based segmentation can be more challenging to develop. It requires quality research. Even after that effort, the criteria can seem ambiguous. The results don’t always bucket neatly into groups that can be aligned with two or more segment leaders. For these reasons, companies often fall back to a segmentation based on easier criteria such as revenue breakpoints or customer age. Such logic is clear for helping companies “divide and conquer,” but those responsible for the resulting initiatives will continually realize they are solving for the same needs, now in operational siloes.

Embrace the Ambiguity, Then Get Personal

The greatest obstacle to fully leveraging segmentation is resistance to ambiguity. Marketers and product designers tend to confine segments to a number that they can keep track of and criteria they can name and shape. It’s common during the process of developing a segmentation to start off with eight to twelve groups, then narrow them down to a more manageable set of four to six. More granularity is more precise and therefore more powerful, but business leaders demand fewer segments so they can understand them and fit them on a page. It’s also easier to define breakpoints based on a business view rather than customers’ needs. Banking clients with $1M+ in assets is an easy group to identify. Within that group are those who reached that point through a life of investing and others who received an inheritance. Their needs are very different. Ironically, the same leaders who limit their segments to numbers and logic they can remember are the same leaders who sponsor personalization projects. Personalization is really about segments of one, where maximal lift occurs not through segmentation but by skipping it altogether. Optimization is driven by analytics and automation, considering every available data point through every touchpoint. The logic and the journeys are far more complex than could be achieved with any number of strategic segments served by manually orchestrated processes.

The forces that make segmentation and personalization seem complex and uncomfortable are here to stay. In fact, they are accelerating. The data points we gather for each customer are expanding in breadth and granularity. Where we used to ask some customers what they did via an occasional survey, now we can track every click and word. Analytic algorithms help us understand customers and then customize their experience. The most powerful algorithms increasingly rely on more advanced methods than the regression techniques many professionals learned in school. More predictive power comes without a line-of-sight to the inner workings. The current advancements in generative AI produce outputs that come without explanation about how the prompt led to the answer given. Traditionally, the value chain for deepening customer relationships through segmentation followed this path: identify customers, group them into segments, develop offerings for each segment and then drive sales with each segment. That’s a legitimate approach that has worked for a long time. It still does in many cases; however new technology enables more powerful methods to the extent product owners can get comfortable with black box algorithms and levels of detail that surpass human comprehension. Once you get over that hurdle, the natural extension is: understand customers then drive sales through orchestrated offers and experiences.

Personalization initiatives attempt to replicate the individual knowledge and tailored treatment we experience through human relationships. There are plenty of spaces where a human’s personal touch is still more effective than any algorithm. Gathering information about medical needs or financial goals is often more effective and more comfortable through an in-person interaction. Sales and services agents can pick up on emotional cues that happen in the moment and influence next steps more than any amount of stored data.

Esther Diener repeatedly discovered valuable customer segments and capitalized on them. She was also a master at personalization. She knew her regulars well. If they were celebrating, she’d treat them to dessert or tear up the bill when presented at the check-out counter. She knew their kids’ birthdays and would sometimes call them to sing the birthday song. The restaurant sold sweet rolls and other baked goods from the check-out area. Esther would occasionally gift her frequent patrons with a free item, a form of loyalty program without a need for terms and conditions, databases criteria or fulfillment tracking. The point of these examples is that segmentation and personalization can both contribute to customer growth. As companies grow, they need increasing technology and scale to continue understanding and meeting their customers’ needs. They also need people, especially people who are skilled at deepening customer relationships and leveraging technology to do it.

Actions to Catalyze Your Success

- Leverage segmentation and personalization to organize and operationalize your customer strategy

- Maximize your results by basing your segments on deep marketing research and modern analytics

- Embrace the ambiguity involved in modern analytics and “black box” automation

- Personalize experiences both through technology and through people

[1] Alfred P. Sloan Jr., My Years with General Motors (New York: Doubleday, 1964), 137, 160. In addition to his simple explanations regarding segmentation and product design, Sloan’s classic provides valuable business insight about the process of innovation, capacity utilization and leadership. After reading it, you’re likely to wonder how we’ve made business so complicated.

This article is provided by Customer Catalytics, a customer analytics and strategy consulting firm. We help companies grow through insight, automation and leadership. For a complimentary consultation focused on your company’s growth needs, contact us or schedule an introductory meeting at www.customercatalytics.com/connect.

© 2024 Customer Catalytics. All rights reserved.